As part of our ongoing series on new problems and ideas in teacher assessments, www.funderstanding.com has reached out to rank-and-file educators for their input. Through both direct sources and a far-reaching social media shout-out, we have spoken to dozens of educators – teachers, specialists and administrators – to gauge their concerns. Not surprisingly, the only obvious consensus is the starting point: a rigorous, fair and valid teacher evaluation system will ultimately result in better student outcomes. Beyond that, any theoretical common ground is laced with divisive practical landmines.

Can administrators effectively do teacher evaluation?

Many teachers expressed concern about the ability of administrators or hired-gun visitors (as opposed to fellow district educators) to fairly and realistically evaluate classroom teachers. Some classroom teachers suggest that the problem with delegating teaching evaluation to principals is twofold: the validity of a non-teacher assessing teaching performance, as well as the potential for creating an adversarial vibe between teachers and administrators. On the first point, Shawn Blankenship, Principal of Dibble Middle School in Dibble, OK, asserts that principals and other administrators are, contrary to the opinion commonly held by many teachers, uniquely qualified to review teaching performance. “Many generic evaluations are very subjective and rely heavily on qualitative data. When I conduct teacher evaluations, however, I use as much quantitative data as possible. It is hard to argue with quantitative data and teachers are more willing to accept constructive criticism if it is measurable. Something I look for is teacher talk vs. student talk. A great ratio to strive for is 70% student talk and 30% teacher talk.” Blankenship also notes that he uses an app to measure this ratio.

On the other hand, J.W., a special education teacher in her state’s top-ranked public high school, suggests that “principals and vice-principals are too far removed from classroom practice to be credible evaluators of our work. They pop in [to each classroom] a couple times a year, and I’m still not clear how or why they could imagine that those few moments could help them understand how well or how poorly we’re doing our jobs.” She claims that she and many of her colleagues share a distrust of the objectivity of the process, and wonder if the traditional hierarchy of teachers, department chairs and admins can implement an assessment process fairly or meaningfully. She posits that a supervisor or department chair tasked with trimming jobs may not assess performance fairly when facing the prospect of losing personnel or laying off friends.

J.W.’s comments also speak to the concern about an us vs. them dynamic pitting teachers against administrators. This is a problem that teachers’ groups recognize as a threat to the communal culture of schools. In its policy paper on teaching evaluation, the National Education Association (NEA) warns that a meaningful assessment “can only occur in non-threatening environments of formative assessment and growth.”

Teacher evaluation by students and parents

A recurring theme among our interview subjects is an interest in bringing students and parents into the evaluation process. As commonsensical as this sounds, this notion is actually revolutionary. When asked to brainstorm about their ideal assessment program, almost every single teacher, administrator and thought leader interviewed included ‘student and parent participation’ in their dream scenario. Tim Bollin, a science teacher at Toledo Early College High School in Ohio and a member of that state’s Educator Standards Board, speaks to this idea. Speaking as a parent and as a teacher, Bollin says that student and parent surveys should be part of any teaching assessment process.

Zac Viscidi just received his undergraduate degree in education last year, and recently completed a student teaching assignment at Cario Middle School in South Carolina. He concurs with many of his teaching colleagues that parents and students must be involved. “The ideal assessment of teachers would be done by parents, students, administrators and fellow teachers. Student surveys of their professors are common in college; why not in public schools? Simple questions can be asked to gather good data. [Such as] What types of assessments did you take? How much homework did you have? How fast did you receive feedback? Data from student evaluations is critical to finding out the amount of work done by teachers. Parents should also be involved because they need to evaluate teachers’ abilities to communicate and address their [the families’] needs.”

Viscidi anticipates Principal Blankenship’s preference for quantitative over qualitative data, and sees no problem incorporating this into a parent/student input format. Parents and, when age-appropriate, students can “provide schools with questionnaires that gauge quantitative data like number of calls per month, involvement, feedback, suggestions. This provides administrators, board members and school leaders with better decision-making ability, because they understand more about a teacher’s input into their district.” Echoing a widespread call for peer review, Viscidi also suggests that “other teachers need to be involved [in professional assessment] because everyone needs to feel comfortable with their co-workers. Finally, principals need more centralized power and oversight. They need to be able to fire any teacher they want, no matter what their tenure status is.”

How does teacher evaluation work in a tenure system?

On this last point, Viscidi has stumbled into the thorny grove of job security. This is the elephant in the teaching evaluation room; how do we fit an assessment system into a world of tenured educators? In school districts all over the country-large and small; urban, suburban and rural; high-achieving and struggling-the confrontation between rigorous assessment and rubber-stamp job renewal is playing out in policy change and political upheaval. Union groups and policy makers are working to reconcile the apparent conflict. Recognizing public impatience with union expectations for tenured educators, unions are showing a willingness to work with their local Boards of Education and other elected officials to implement more consequential evaluation programs among their members. At its annual conference last month, the 3.2 million-member NEA addressed the issue of teaching quality head-on and acknowledged that student performance must be taken into account when assessing teaching performance.

Young teachers are aware of the folly of entitlement that accompanies tenure. Viscidi, in his argument for administrative oversight for principals, notes, “I know about the so-called ‘Dance of the Lemons,’ the swapping of bad teachers. Firing teachers needs to be easy, but not necessarily punitive. Instead of firing teachers found ineffective, we need to see why they are ineffective. Ideally, there is another situation that better suits them. There should be no stigma attached to being re-assigned to work in a different district under different management styles.”

Best teacher evaluation system

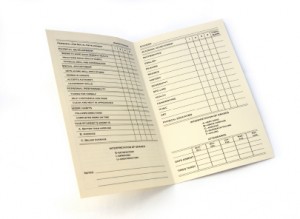

Veteran teacher Tim Bollin also acknowledges the political realities that render each school unique, and suggests an assessment program that accounts for those distinctions. His ideal method would take into account many different sources of input. “Teachers should cover the standards, of course, but also be effective in other areas. [An evaluation system] should look at not only content area, but also parent and student input, whole school data -the collaborative climate of the school and its staff-a standards-based report card that would look at multiple criteria in multiple ways. Also, peer evaluation is as important if not more so than administrative.” Finally, Bollin suggests, SAT/ACT test would be acceptable forms of standardized testing to factor into teaching performance at the high school level. He is comfortable with those specific tests as evaluative tools, he says, because they have been shown to be predictive of college success. This notion of incorporating standardized test scores into teaching assessments is a tangled mess. Like many hot-button issues, this one is ripe for statistical manipulation. Every party to the teaching evaluation debate supports, in theory, the need to use some standardized student performance data as part of the matrix. But what data, and how it was collected, and what it means, and how much it should weigh, and how reliably it was gathered-all of those points are subject to debate and distrust.

Using rubrics for teaching assessment

Qualitative vs quantitative data. On this topic, a considerable number of academics and administrators responded to our queries with two words: Charlotte Danielson. Danielson’s rubric, “A Framework for Teaching,” outlines four domains and their attendant tasks, and provides definitions for unsatisfactory, emergent, proficient and distinguished practitioners in each area. Viscidi, Blankenship, Weil and others we spoke to cited this rubric as a jumping-off point for any meaningful teaching evaluation system. That being said, even applying a well-written rubric is a matter of art, not science. That is to say, the measurement is still being done by human beings, with all the subjectivity and imprecision that that implies.

Teacher evaluation as a collaborative effort

“Collaboration” is a word that pops up frequently among thought leaders in the field. American Federation of Teachers (AFT) Director of Field Programs Rob Weil, a former high school math teacher who left the classroom after more than twenty years to spearhead the AFT’s professional assessment policy development, is a cheerleader for collaboration. Weil has become a student of international models of teaching assessment, and notes that in many Asian countries “lesson study,” a sanctioned and scheduled time within the school day schedule for collaborative efforts among faculty, “results in more effective classroom teaching. ” The other behemoth union, the NEA, stresses that “safe and open collaboration is necessary. When assessment of teacher practices is transparent and openly collaborative, teachers can build professional communities and learn from one another.”